CHILDREN OF THE MASSACRE

MISCELLANEOUS HISTORICAL RECONSTRUCTIONS

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Links to more early MMM Texts | Home

1868: C. V. Wait | 1873: T. B. H. Stenhouse | 1908: H. P. Freece | 1914: R. N. Baskin

1922: J. F. Smith | 1925: M. R. Werner | 1957: R. B. West | 1993: LDS Church

|

Extract from C. V. Waite (1866-8) pp. 60-88

The darkest chapter of Mormon history is now before us. It becomes my duty to relate one of the most perfidious acts of cruelty and wholesale butchery to be found in the annals of this or any other country. In doing so, free use will be made of the statements of Judge Cradlebaugh and others who were thoroughly conversant with all the facts. The following is from the able speech of Judge Cradlebaugh, delivered in the House of Representatives on the 7th of February, 1863: "As one of the Associate Justices of the Territory of Utah, in the month of April, 1859, I commenced and held a term of the District Court for the Second Judicial District, in the city of Provo, about sixty miles south of Salt Lake City. Upon my requisition, Gen. A. S. Johnson, in command of the military department, furnished a small military force for the purpose of protecting the court. A grand jury was empanelled, and their attention was pointedly and specifically called to a great number of crimes that had been committed in the immediate vicinity, cases of public notoriety, both as to the offence and the persons who had perpetrated the same; (for none of these things had 'been done in a corner'). Their perpetrators had scorned alike concealment or apology, before the arrival of the American forces. The jury thus instructed, though kept in session two weeks, utterly [Waite, 1868: p. 61] refused to do anything, and were finally discharged, as an evidently useless appendage of a court of justice. But the court was determined to try a last resource, to bring to light and to punishment those guilty of the atrocious crimes which confessedly had been committed in the Territory, and the session continued. Bench warrants, based upon sworn information, were issued against the alleged criminals, and United States Marshal Dotson, a most excellent and reliable officer, aided by a military posse, procured on his own request, had succeeded in making a few arrests. A general stampede immediately took place among the Mormons, and what I wish to call your attention to, as particularly noticeable, is the fact that this occurred more especially among the church officials and civil officers. * * * "Sitting as a committing magistrate, complaint after complaint was made before me of murders and robberies. Among these I may mention, as peculiarly and shockingly prominent, the murder of Forbes, the assassination of the Parrishes and Potter, of Jones and his mother, of the Aiken party, of which there were six in all; and, worst and darkest in the appalling catalogue of blood, the cowardly, cold-blooded butchery and robbery at the Mountain Meadows. At that time there still lay, all ghastly, under the sun of Utah, the unburied skeletons of one hundred and nineteen men, women, and children, the hapless, hopeless victims of the Mormon creed. * * * "The scene of this horrible massacre at the Mountain Meadows is situate about three hundred and twenty miles west of south from Great Salt Lake City, on the road leading to Los Angeles, in California. I was the first federal Judge in that part of the Territory after the occurrence, my district extending from a short distance below Salt Lake City to the south end of the Territory. I determined to visit that part of my district, and, if possible, expose the persons engaged in the massacre, which I did in the early part of the year 1859. I accordingly embraced an opportunity of accompanying a small detachment of soldiers, who were being sent to that section by Gen. Johnson, having requested the Marshal of the Territory to accompany, or to send a deputy. He accordingly sent deputy William H. Rodgers, who went with me. "The command went as far south as the St. Clara, twenty miles beyond the Mountain Meadows, where we camped, and remained [Waite, 1868: p. 62] about a week. During our stay there I was visited by the Indian chiefs of that section, who gave me their version of the massacre. They admitted that a portion of their men were engaged in the massacre, but were not there when the attack commenced. One of them told me, in the presence of the others, that after the attack had been made, a white man came to their camp with a piece of paper, which, he said, Briyham Young had sent, that directed them to go and help to whip the emigrants. A portion of the band went, but did not assist in the fight. He gave as a reason, that the emigrants had long guns, and were good shots. He said that his brother [this chief's name was Jackson] was shot while running across the Meadow, at a distance of two hundred yards from the corral where the emigrants were. He said the Mormons were all painted. He said the Indians got a part of the clothing; and gave the names of John D. Lee, President Haight, and Bishop Higbee, as the big captains. It might be proper here to remark that the Indians in the southern part of the Territory of Utah are not numerous, and are a very low, cowardly, beastly set, very few of them being armed with guns. They are not formidable. I believe all in the southern part of the Territory would, under no circumstances, carry on a fight against ten white men. "From our camp on the St. Clara we again went back to the Mountain Meadows, camping near where the massacre had occurred. The Meadow is about five miles in length and one in width, running to quite a narrow point at the southwest end, being higher at the middle than either end. It is the divide between the waters that flow into the Great Basin and those emptying into the Colorado River. A very large spring rises in the south end of the narrow part. It was on the north side of this spring the emigrants were camped. The bank rises from the spring eight or ten feet, then extends off to the north about two hundred yards, on a level. A range of hills is there reached, rising perhaps fifty or sixty feet. Back of this range is quite a valley, which extends down until it has an outlet, three or four hundred yards below the spring, into the main meadow. "The first attack was made by going down this ravine, then following up the bed of the spring to near it, then at daylight firing upon the men who were about the camp-fires, in which attack ten or twelve of the emigrants were killed or wounded; [Waite, 1868: p. 63] the stock of the emigrants having been previously driven behind the hill, and up the ravine. "The emigrants soon got in condition to repel the attack, shoved their wagons together, sunk the wheels in the earth, and threw up quite an intrenchment. The fighting after continued as a siege; the assailants occupying the hill, and firing at any of the emigrants that exposed themselves, having a barricade of stones along the crest of the hill as a protection. The siege was continued for five days, the besiegers appearing in the garb of Indians. The Mormons, seeing that they could not capture the train without making some sacrifice of life on their part, and getting weary of the fight, resolved to accomplish by strategy what they were not able to do by force. The fight had been going on for five days, and no aid was received from any quarter, although the family of Jacob Hamlin, the Indian agent, were living in the upper end of the Meadow, and within hearing of the reports of the guns. "Who can imagine the feelings of these men, women, and children, surrounded, as they supposed themselves to be, by savages? Fathers and mothers only can judge what they must have been. Far off, in the Rocky Mountains, without transportation, for their cattle, horses and mules had been run off, -- not knowing what their fate was to be, -- we can but poorly realize the gloom that pervaded the camp. "A wagon is descried, far up the Meadows. Upon its nearer approach, it is observed to contain armed men. See! now they raise a white flag! All is joy in the corral. A general shout is raised, and in an instant, a little girl, dressed in white, is placed at an opening between two of the wagons, as a response to the signal. The wagon approaches; the occupants are welcomed into the corral, the emigrants little suspecting that they were entertaining the fiends that had been besieging them. "This wagon contained President Haight and Bishop John D. Lee, among others of the Mormon Church. They professed to be on good terms with the Indians, and represented the Indians as being very mad. They also proposed to intercede, and settle the matter with the Indians. After several hours of parley, they, having apparently visited the Indians, gave the ultimatum of the Indians; which was, that the emigrants should march out of their camp, leaving everything behind them, even their guns. It was [Waite, 1868: p. 64] promised by the Mormon bishops that they would bring a force, and guard the emigrants back to the settlements. "The terms were agreed to, the emigrants being desirous of Saving the lives of their families. The Mormons retired, and subsequently appeared at the corral with thirty or forty armed men. The emigrants were marched out, the women and children in front, and the men behind, the Mormon guard being in the rear. When they had marched in this way about a mile, at a given signal, the slaughter commenced. The men were most all shot down at the first fire from the guard. Two only escaped, who fled to the desert, and were followed 150 miles before they were overtaken and slaughtered. "The women and children ran on, two or three hundred yards further, when they were overtaken, and with the aid of the Indians they were slaughtered. Seventeen only of the small children were saved, the eldest being only seven years. Thus, on the 10th day of September, 1857, was consummated one of the most cruel, cowardly, and bloody murders known in our history. Upon the way from the Meadows, a young Indian pointed out to me the place where the Mormons painted and disguised themselves. "I went from the Meadows to Cedar City; the distance is thirty-five or forty miles. I contemplated holding an examining court there, should Gen. Johnson furnish me protection, and also protect witnesses, and furnish the Marshal a posse to aid in making arrests. While there I issued warrants, on affidavits filed before me, for the arrest of the following named persons: "Jacob Haight, President of the Cedar City Stake; Bishop John M. Higbee and Bishop John D. Lee; Columbus Freeman, William Slade, John Willis, William Riggs, _____ Ingram, Daniel McFarlan, William Siewart, Ira Allen and son, Thomas Cartwright, E. Welean, William Halley, Jabes Nomlen, John Mangum, James Price, John W. Adair, _____ Tyler, Joseph Smith, Samuel Pollock, John McFarlan, Nephi Johnson, _____ Thornton, Joel White, _____ Harrison, Charles Hopkins. Joseph Elang, Samuel Lewis, Sims Matheney, James Mangum, Harrison Pierce, Samuel Adair, F. C. McDulange, Wm. Bateman, Ezra Curtis, and Alexander Loveridge. "In a few days after arriving at Cedar City, Capt. Campbell arrived, with his command, from the Meadows; on his return, he advised me that he had received orders, for his command entire, [Waite, 1868: p. 65] to return to Camp Floyd; the General having received orders from Washington that the military should not be used in protecting the courts, or in acting as a posse to aid the Marshal in making arrests. "While at Cedar City I was visited by a number of apostate Mormons, who gave me every assurance that they would furnish an abundance of evidence in regard to the matter so soon as they were assured of military protection. In fact, some of the persons engaged in the act came to sec me in the night, and gave a full account of the matter, -- intending when protection was at hand, to become witnesses. They claimed that they had been forced into the matter by the bishops. Their statements corroborated what the Indians had previously said to me. Mr. Rodgers, the Deputy Marshal, was also engaged in hunting up the children, survivors of the massacre. They were all found in the custody of the Mormons. Three or four of the eldest recollect and relate all the incidents of the massacre, corroborating the statements of the Indians, and the statements made by the citizens of Cedar City to me. "These children are now in the south part of Missouri, or north part of Arkansas; their testimony could soon be taken, if desired. No one can depict the glee of these infants, when they realized that they were in the custody of what they called 'the Americans,' -- for such is the designation of those not Mormons. They say they never were in the custody of the Indians. I recollect of one of them, 'John Calvin Sorrow,' after he found he was safe, and before he was brought away from Salt Lake City, although not yet nine years of age, sitting in a contemplative mood, no doubt thinking of the extermination of his family, saying: 'Oh, I wish I was a man; I know what I would do; I would shoot John D. Lee; I saw him shoot my mother.' I shall never forget how he looked. "Time will not permit me to elaborate the matter. I shall barely sum up, and refer every member of this House, who may have the least doubt about the guilt of the Mormons in this massacre, and the other crimes to which I have alluded, to the evidence published in the appendix hereto." To the foregoing thrilling recital, I will only add: The train consisted of 40 wagons, 800 head of cattle, and about 60 horses and mules. As near as can be ascertained, there [Waite, 1868: p. 66] were about 150 men and women, besides many children. They passed through Salt Lake City, and were there joined by some few Mormons, who were disaffected, and sought to travel under their protection. A revelation from Brigham Young, as Great Grand Archee, or God, was despatched to President J. C. Haight, Bishop Higbee, and J. D. Lee, commanding them to raise all the forces tbey could muster and trust, follow those cursed gentiles (so read the revelation), attack them, disguised as Indians, and with the arrows of the Almighty make a clean sweep of them, and leave none to tell the tale; and if they needed any assistance, they were commanded to hire the Indians as their allies, promising them a share of the booty. They were to be neither slothful nor negligent in their duty, and to be punctual in sending the teams back to him before winter set in, for this was the mandate of Almighty God. On the following day a council of all the faithful was held at Cedar City. Many attended from the neighboring settlements; the revelation was read, and the destiny of the unsuspecting emigrants sealed. Plans were suggested, discussed, and adopted, and the men designated to carry out their hellish designs. Instructions were given for them to assemble at a small spring, but a short distance to the left of the road leading into the Meadows, -- a number of intervening hills rendering it a fit place for concealment. Here they painted and disguised themselves as Indians, and when ready to commence operations, by a well-known Indian trail proceeded to the Meadows. For the benefit of those who may still be disposed to doubt the guilt of Young and his Mormons in this transaction, the testimony is here collated, and circumstances given, which go, not merely to implicate, but to fasten conviction upon them, by "confirmations strong as proofs from Holy Writ," 1. The evidence of Mormons themselves, engaged in the [Waite, 1868: p. 67] affair, as shown by the statements of Judge Cradlebaugh and Deputy-Marshal Rodgers. 2. The statements of Indians in the neighborhood of the massacre: these statements are shown, not only by Cradlebaugh and Rodgers, but by a number of military officers, and by J. Forney, who was, in 1859, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Territory. To all these were such statements freely and frequently made by the Indians. 3. The testimony of the children saved from the massacre. 4. The children and the property of the emigrants found in possession of the Mormons, and that possession traced back to the very day after the massacre. 5. The failure of Brigham Young to embody any account of it "in his Report as Superintendent of Indian Affairs. Also his failure to make any allusion to it whatever from the pulpit, until several years after the occurrence. 6. The failure of the "Deseret News," the Church organ, and the only paper then published in the Territory, to notice the massacre, until several months afterward, and then only to deny that Mormons were engaged in it. 7. The flight to the mountains of men high in authority in the Mormon Church and State, when this affair was brought to the ordeal of a judicial investigation. 8. The testimony of R. P. Campbell, Capt. 2d Dragoons, who was sent in the spring of 1859 to Santa Clara, to protect travellers on the road to California, and to inquire into Indian depredations. In his report to Major E. J. Porter, Assistant Adjutant General U. S. Army, dated July 6, 1859, he says: -- "These emigrants were here met by the Mormons (assisted by such of the wretched Indians of the neighborhood as they could force or persuade to join), and massacred, with the exception of such infant children as the Mormons thought too young to remember, or tell of the affair. "The Mormons were led on by John D. Lee, then a high dignitary in the self-styled Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, and Isaac Haight, now a dignitary in the same." [Waite, 1868: p. 68] Again, after relating briefly the massacre, he says: "These facts were derived from children who did remember, and could tell of the matter; from Indians, and from the Mormons themselves." 9. The testimony of Hon. J. Forney, Superintendent of Indian Affairs. In his letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs at Washington, dated Provo City, U. T., March, 1859, he says: "Facts in my possession warrant me in estimating that there was distributed, a lew days after the massacre, among the leading church dignitaries, $30,000 worth of property." Again, in another letter to the Commissioner, written from Great Salt Lake City, in August of the same year, he says: "From the evidence in my possession, I am justified in the declaration that this massacre was concocted by white men, and consummated by whites and Indians. The names of many of the whites engaged in this terrible affair have already been given to the proper legal authorities.... The children were sold out to different persons in Cedar City, Harmony, and Painter Creek. Bills are now in my possession from different individuals, asking payment from the Government. I cannot condescend to become the medium of even transmitting such claims to the Department." The following is from the Annual Report of Superintendent Forney, made in September, 1859: "Mormons have been accused of aiding the Indians in the commission of this crime. I commenced my inquiries without prejudice or selfish motive, and with the hope that, in the progress of my inquiries, facts would enable me to exculpate all white men from any participation in this tragedy, and saddle the guilt exclusively on the Indians; but, unfortunately, every step in my inquiries satisfied me that the Indians acted only a secondary part. * * * White men were present, and directed the Indians. John D. Lee, of Harmony, told me in his own house, last April, in [Waite, 1868: p. 69] presence of two persons, that he was present three successive days during the fight, and was present during the fatal day." * * * We close the testimony of Forney, by giving entire a letter from him to the Department at Washington, "SUPERINTENDENT'S OFFICE, UTAH, GREAT SALT LAKE CITY, September 22, 1859. "Sir, -- Your letter dated July 2, in which you request me to ascertain the names of white men, if any, implicated in the Mountain Meadow massacre, reached me several weeks since, about 300 miles west of this city. "I gave, several months ago, to the Attorney-General, and several of the United States Judges, the names of those who I believed were not only implicated, but the hell-deserving scoundrels who concocted and brought to a successful termination the whole affair. "The following are the names of the persons the most guilty: Isaac T. Haight, Cedar City, president of several settlements south; Bishop Smith, Cedar City; John D. Lee, * Harmony; John M. Higby, Cedar City; Bishop Davis, David Tullis, Santa Clara; Ira Hatch, Santa Clara. These were the cause of the massacre, aided by others. It is to be regretted that nothing has yet been accomplished towards bringing these murderers to justice. I remain, "Very respectfully, your obedient servant, "J. FORNEY, "Sup't of Indian Affairs, Utah Territory. "Hon. A. B. Greenwood, "Commiss'r Indian Affairs, Washington, D. C." So far as Brigham Young himself is concerned, the evidence is not so direct, but is scarcely less conclusive. In addition to the circumstances mentioned, of his failing to report the massacre, or to make any mention of it in his public discourses, and the testimony of the Indians, already referred to; in addition also to the facts concerning the revelation sent from him, -- facts communicated by one intimately acquainted with the secret history of the church; in addition __________ * John D. Lee is an adopted son of Brigham Young. [Waite, 1868: p. 70] to these things, if we reflect for a moment upon the framework of the Mormon Church, we will find therein still more cogent evidence. The organization of the church is such, that no project of importance is ever undertaken wiihout the express or implied consent of Young, who is in temporal, as well as spiritual matters, the head and source of all authority. Now here was a large train which had lately passed through the place where Young resided, and his feelings and views in relation to it would be well known to the leaders of the church. Can it for a moment be admitted, that members of a community so organized would undertake so important a project as the destruction of that train, requiring, as it did, the concerted action of forty or fifty persons, without the express or implied sanction of him who sat at the head of the community, controlling its every action? And if such a thing can be supposed possible, would not the perpetrators be immediately called to account for asuming so much responsibility? Reason and evidence all point one way; and add this to the many other acts which stamp Brigham Young as a murderer of the deepest dye, adding to the guilt of homicide that of blasphemy and hypocrisy. What was the motive which prompted the act? Partly revenge. These emigrants were from Missouri and Arkansas, the scenes of the alleged injuries and persecutions of the Mormons. It was soon after the killing of Parley P. Pratt, in Arkansas, by McLane [sic], whose wife Pratt had abducted. It was at the time, too, when the United States troops were marching to Utah, and a feeling of revenge and retaliation was prevalent, and was, as has been shown, fostered and encouraged by Brigham in his sermons. But the principal motive was plunder. The train was a very wealthy one. The spoil of the gentile was before them, and it must be appropriated by the Lord's people. A great portion of the property was taken to Cedar City, [Waite, 1868: p. 71] deposited in the tithing office, and there sold out. Forney says, in the Annual Report already quoted from, "Whoever may have been the perpetrators of this horrible deed, no doubt exists in my mind that they were influenced chiefly by a determination to acquire wealth by robbery." * It is not within the scope of this work to enter into a relation of the many other murders and outrages committed by the authority or connivance of the Mormon Church. This is given as the most notable one, "ex uno disce omnes" Those who wish to examine into these crimes more fully, are referred to the appendix to the printed speech of Judge Cradlebaugh. The "Mormon War" having closed, the federal officers, as soon as practicable, assumed their functions, and proceeded to transact business. Federal courts were held, and the authority of the United States again, at least nominally, established in Utah. In October, 1858, Judge Sinclair opened his court in Salt Lake City. Efforts were made to bring several noted criminals to justice, but everything failed. In the grand jury-room no indictments were found, and murderers and thieves were allowed to go "scot free." At this term of court a motion was made to expel James Ferguson from the bar, for contempt of court. Ferguson offered to retire from the bar, which was not accepted. He then proposed to plead guilty; but the Judge said, as it was alleged that a Judge of the United States had been insulted __________ * Several years after the massacre, Major, now General Carlton, visited that region and erected a monument to the memory of the slain. "It was constructed by raising a large pile of rock, in the centre of which was erected a beam, some twelve or fifteen feet in height. Upon one of the stones he caused to be engraved, 'Here lie the bones of one hundred and twenty men, women, and children, from Arkansas, murdered on the 10th day of September, 1857.' Upon a cross-tree, on the beam, he caused to be painted: 'Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord, and I will repay it.' This monument is said to have been destroyed the first time Brigham visited that part of the Territory." |

|

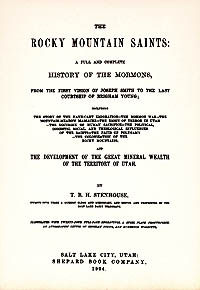

Extract from T. B. H. Stenhouse (1873) pp. 424-28

The latter company was wealthy, and there were around them every indication of comfort, and everything in abundance for pleasant travelling. In addition to the ordinary transportation wagons of emigrants, they had several riding carriages, which betokened the social class of life in which some of the emigrants had moved before setting out on the adventure of western colonization. [Stenhouse, 1873: p. 427] They were in no hurry, but travelled leisurely, with the view of nursing the strength of their cattle, horses, and mules, in order to accomplish successfully the long and tedious journey which they had undertaken. In that company there were men, women, and children, of every age, from the venerable patriarch to the baby in arms. It was a bevy of families related to each other by the ties of consanguinity and marriage, with here and there in the train a neighbour who desired to share with them the chances of fortune in the proposed new homes on the golden shores of the Pacific. One of their number had been a Methodist preacher, and probably most of the adults were members of that denomination. They were moral in language and conduct, and united regularly in morning and evening prayers. On Sundays they did not travel, but observed it as a day of sacred rest for man and beast. At the appointed hour of service, this brother-preacher assembled his fellow-travellers in a large tent, which served as a meeting-house, within their wagon-circled camp, for the usual religious exercises, and there, on the low, boundless prairies, or in higher altitudes at the base of snow-capped mountains, he addressed them as fervently, and with as much soul-inspiring faith, as if his auditory had been seated comfortably within the old church-walls at home, and they too sang their hymns of praise with grateful, feeling souls, and with hearts impressed with the realization that man was but a speck in the presence of that grand and limitless nature that surrounded them, and of which they were but a microscopic part. Those who passed the company en route, or travelled with them a part of the way, were favourably impressed with their society, and spoke of them in the kindest terms as an exceedingly fine company of emigrants, such as was seldom seen on the plains. Though utterly unlike themselves in character and disposition, the "Wild-cats" contracted for them much respect, and came as near to them in travelling as was convenient for the grazing of the cattle and the purposes of the camp at night. Within sight of each other they would form their corrals, but, while the one resounded with vulgar song, boisterous roaring, [Stenhouse, 1873: p. 428] and "tall swearing," in the other there was the peace of domestic bliss and conscious rectitude. A gentleman, a friend of the Author, travelled with this Arkansas company from Fort Bridger to Salt Lake City, and speaks of them in the highest terms: he never travelled with more pleasant companions. Hearing the nightly yells of the "Wild-cats," he advised the Arkansas company to separate from them as much as possible while passing through the settlements, and in going through the Indian country. At that time it was easy to provoke a difficulty; the whole country was excited over the news of the "invading army;" and so much was this gentleman impressed with the necessity of great prudence on the part of the emigrants that, after he had left them on his arrival at Salt Lake City, he afterwards returned and impressed upon the leading men the urgency of refusing to travel further with the Missouri company so near to them. The kindly suggestions were appreciated, and they expressed their desire to act upon them. Up to tin's time the journey of the emigrants had been prosperous, and everything bade fair for a pleasant termination of their travels. Like all other pilgrims, they had counted upon replenishing their stock of provisions at Salt Lake City, and to do tins, and to rest their cattle, they concluded to camp awhile by the Jordan.... (read more of T. B. H. Stenhouse's account, from Ch. 43 of his 1873 Rocky Mountain Saints.) |

|

Extract from M. R. Werner (1925) pp. 398-417

In order to understand the Mountain Meadows Massacre, it is first necessary to realize the state of mind of the Mormons during 1856 and 1857. During the year 1856 there took place, under the leadership of Brigham Young and his fiery associate, Jedediah M. Grant, what is known in the Mormon Church as the Reformation. There had been during 1854 and 1855 a period of dangerous famine and intense hard times. This led some of the people to leave the valley of the Great Salt Lake and its crickets, grasshoppers, and drought, for California, where there were gold, warm days, and rich soil. Many Mormons were induced by the contrast with their own lot, however temporary their leaders insisted it was, and what seemed to be the eternal golden prosperity of nearby California, to abandon their religion for the ease and comfort of this world. The religious community was thereby threatened with partial disintegration, and the leaders were thereby led to use exhortation, persuasion, and, finally, compulsion, to keep their people in what they sternly and sincerely believed were the paths of righteousness. Famine and hard times had also led to quarrels among the Saints about property and about wives. [Werner, 1925: p. 399] Obedience to Brigham Young's will was not so general as he wished and as he had been in the habit of expecting. Therefore, he and his associates, Jedediah Grant and Heber Kimball, decided to bring the people to a realization of the value of virtue by vigorous action against vice. For one thing, the Saints had begun to ignore the Sabbath. The wars against grasshoppers and crickets had made it necessary to work sometimes on Sunday, and this led quickly to a habit of mind that regarded Sunday as the same as every other day. Then, too, the strong community spirit had inculcated in some men the habit of regarding their neighbor's ox or his ass as their own, especially if they happened at the moment to be in great need of an ox or an ass. This soon developed into the same attitude toward a neighbor's wife. It is said that at a meeting of the principal members of the priesthood, Brigham Young said in the course of a harangue: "All you who have been guilty of committing adultery, stand up." To his amazement and chagrin three-fourths of the brethren present promptly stood up. It was explained that Brother Brigham had meant, of course, that only those who bad committed adultery since they became Mormons need stand. All the guilty brethren remained standing. Brigham Young was overwhelmed, and he prescribed immediate baptism for the remission of sins, and it was made clear that after this batch of sins had been washed away, they could be forgotten and need never again be acknowledged so publicly. Brigham H. Roberts, assistant historian of the Church, in discussing what he termed the "sex sins" of the community, wrote: "The unsettled life of the ten years between the exodus from Nauvoo and the beginning of 'the Reformation' was crowded with circumstances that lent themselves to continuous temptations in this kind of evil. There were the long weeks of ocean travel by mixed companies in slow-sailing vessels; followed by long journeys of the same mixed companies up the American rivers, in crowded steamboats; or day and night travel in more crowded railway trains to the western terminal of the railroads. Then there was the longer overland journeying by hand cart or ox train means of travel, all classes being thrown into constant and closest contact, which not all the care of the organized camp, nor the watchfulness of faithful pastors could rob of insidious and sometimes ruinous temptations." [1] __________ 1 Americana, vol. 8, pp. 459-462. [Werner, 1925: p. 400] Brigham Young, with Yankee enthusiasm, declared in a sermon one Sunday that not only were the Mormons "the best looking and finest set of people on the face of the earth," not only could they "pray the best, preach the best, sing the best," but also that they had among them "the greatest and smoothest liars in the world, the cunningest and most adroit thieves, and any other shade of character that you can mention." He said that the Gospel net dragged in all kinds of fish, and that many of them proved, upon closer inspection, to be rotten. Several times Brigham Young had said in the pulpit that those who wished to leave the Saints were free to do so if they paid their debts. What Brigham Young resented, however, was the action of apostates after they had left the Church. Apostates had done the Mormons so much harm with their enemies in Missouri and Illinois that Brigham Young had come to fear and to hate them for the tales they now told in California and in the East. It was determined during the Reformation to exercise as much intimidating control over the dissatisfied as possible, and this control in the last extremity extended sometimes to murder. There was, for example, the case of William Parrish, who had been one of the trusted members of the Church in Nauvoo. He became dissatisfied in Utah and made secret plans to leave for California. At the suggestion of Brigham Young, who knew everybody's plans before they were consummated, Bishop Johnson looked into Parrish's intentions. The Bishop visited Parrish with two other agents of the Church, Durfee and Potter, and they gained his confidence by professions of their own dissatisfaction and by promises of aid. A week later Parrish's horses were stolen. Finally, Durfee and Potter planned to aid Parrish to leave Utah. They arranged with him to meet him outside the city, and when they bad met, Durfee returned to Salt Lake City to get Parrish's two sons, Orrin and Beason. While Parrish and Potter were waiting for Durfee and the young boys, William Bird, who was lying in hiding, fired a shot, which by mistake hit Potter instead of Parrish. Potter died. Bird came into the open, and when Parrish asked him if he had killed Potter, he drew a bowie knife and stabbed Parrish fifteen times in the back, sides, and arms. Bird returned to his hiding-place, and when Durfee returned with Parrish's two sons, William Bird from his ambush shot Beason dead and tried to kill Orrin, who escaped after the first shot hit his cartridge box. [Werner, 1925: p. 401] There were other cases of murder, not so well substantiated as the Parrish case, which was fully investigated by the federal official, judge Cradlebaugh. It is clear that Brigham Young and his associates had aroused themselves to the point of fanaticism in their determination to keep men righteous by any means, and to prevent them from telling tales if they could not be kept faithful. It is claimed that during this wave of fanaticism men were not only murdered, but were sometimes flogged, and often castrated. How much of this was true, it is impossible to determine, but that some of it was true is easily discerned from the sermons of the time and the confessions of former Mormons. John D. Lee wrote: "In Utah it has been the custom of the Priesthood to make eunuchs of such men as were obnoxious to the leaders. This was done for a double purpose: first, it gave a perfect revenge, and next, it left the poor victim a living example to others of the dangers of disobeying counsel and not living as ordered by the Priesthood." Lee also maintained that, "In Utah it was the favorite revenge of old, worn-out members of the Priesthood, who wanted young women sealed to them, and found that the girl preferred some handsome young man. The old priests generally got the girls, and many a young man was unsexed for refusing to give up his sweetheart at the request of an old and failing, but still sensual apostle or member of the Priesthood." [2] Another of Brigham Young's henchmen, who wrote his confessions, was Bill Hickman. He was a man who never objected to killing another man, if be felt that the man deserved to be dead, or if he was convinced that the act was necessary to preserve either himself or his Church from danger or inconvenience. When a man he was about to hang for murder told Hickman he would come back and haunt him for the rest of his life, Hickman calmly replied, "I am not much afraid of live men, and much less of dead ones." Bill Hickman was known for many years as Brigham Young's Destroying Angel. In his book Hickman recorded his murders and his scalpings with a charming lack of bravado, shame, or sentimentality. He rarely implicates Brigham Young directly, but he intimates that in some instances the President __________ 2 Mormonism Unveiled, by John D. Lee, p. 284. It is necessary to note that Lee's book was touched up by his lawyer, W. W. Bishop, who claimed that be only altered a word or straightened a sentence here and there. But it is possible that in the process he heightened an effect. [Werner, 1925: p. 402] of the Church let it be known that a man was undesirable, and then allowed Hickman to use his own violent judgment on the case. Hickman was capable of beating a man to death with the butt end of his rifle, literally without thinking about it afterwards, and he was at one time firmly convinced that anything Brigham Young ordered was just, and that in return for obedience he would receive eternal spiritual salvation. Hickman was only one of the executioners of the Reformation, but Jedediah Grant was its firebrand. "As for you miserable, sleepy 'Mormons,' " Grant said in a sermon, "who say to those wretches, [the Gentiles] 'Give us your dimes, and you shall have our wheat, and our daughters, only give us your dimes and you shall have this, that, and the other,' I not only wish but pray, in the name of Israel's God, that the time was come in which to unsheathe the sword, like Moroni of old, and to cleanse the inside of the platter, and we would not wait for the decision of grand or traverse juries, but we would walk into you and completely use tip every curse who will not do right." [3] Brigham Young had decided that the time had come to unsheathe the sword, and for "judgment to be laid to the line and righteousness to the plummet." For this purpose he brought forth the most appalling theory of Mormon theology, the doctrine of blood atonement for sins. According to this theory, there exist certain sins for which atonement can only be had by shedding the blood of the sinners. Among these sins were apostasy, unfaithfulness to the marriage obligations on the part of the wife, and the shedding of innocent blood. In a sermon Brigham Young once explained the theory to the congregation, whom he hoped to reform: "There are sins that men commit for which they cannot receive forgiveness in this world, or in that which is to come, and if they had their eyes open to see their true condition, they would be per- fectly willing to have their blood spilt upon the ground, that the smoke thereof might ascend to heaven as an offering for their sins; and the smoking incense would atone for their sins, whereas, if such is not the case, they will stick to them and remain upon them in the spirit world. "I know, when you bear my brethren telling about cutting people off from the earth, that you consider it is strong doctrine; but it is to save them, not to destroy them. __________ 3 Journal of Discourses, vol. 3, p. 235. [Werner, 1925: p. 403] "I do know that there are sins committed, of such a nature that if the people did understand the doctrine of salvation, they would tremble because of their situation. And furthermore, I know that there are transgressors, who, if they knew themselves, and the only condition upon which they can obtain forgiveness, would beg of their brethren to shed their blood, that the smoke thereof might ascend to God as an offering to appease the wrath that is kindled against them, and that the law might have its course. I will say further; I have had men come to me and offer their lives to atone for their sins. "It is true that the blood of the Son of God was shed for sins through the fall and those committed by men, yet men can commit sins which it can never remit. As it was in ancient days, so it is in our day; and though the principles are taught publicly from this stand, the people do not understand them; yet the law is precisely the same. There are sins that can be atoned for by an offering upon an altar, as in ancient days; and there are sins that the blood of a lamb or a calf, or of turtle doves, cannot remit, but they must be atoned for by the blood of the man." And in another sermon Brigham Young emphasized that true love was a love that would shed blood in order to insure for the loved one eternal salvation: "All mankind," he said, "love themselves, and let these principles be known by an individual, and he would be glad to have his blood shed. That would be loving themselves, even unto an eternal exaltation. Will you love your brothers or sisters likewise, when they have committed a sin that cannot be atoned for without the shedding of their blood? Will you love that man or woman well enough to shed their blood? That is what Jesus Christ meant. He never told a man or woman to love their enemies in their wickedness, never.... "I have seen scores and hundreds of people for whom there would have been a chance (in the last resurrection there will be) if their lives had been taken and their blood spilled on the ground as a smoking incense to the Almighty, but who are now angels to the devil, until our elder brother Jesus Christ raises them up -- conquers death, hell, and the grave. I have known a great many men who have left this Church for whom there is no chance whatever for exaltation, but if their blood had been spilled, it would have been better for them. The wickedness and ignorance of the nations forbid this principle's being in full force, but the time will come when the law of God will be in full force. __________ 4 Journal of Discourses, vol. 4, pp. 53-54. [Werner, 1925: p. 404] "This is loving our neighbor as ourselves; if he needs help, help him; and if he wants salvation and it is necessary to spill his blood on the earth in order that he may be saved, spill it. Any of you who understand the principles of eternity, if you have sinned a sin requiring the shedding of blood, except the sin unto death, would not be satisfied nor rest until your blood should be spilled, that you might even gain that salvation you desire. That is the way to love mankind." [5] This was the height of fanatical Puritanism. The world to come, with its promise of eternal salvation and unsurpassable glory, was everything, and this world with its joys and amusements was correspondingly insignificant. The doctrine of blood atonement was a terrible doctrine, and the fact that there are few instances of its actual practice, does not detract from its philosophical terror. Brigham Young was now beginning to lose patience with mankind because it just would not be saved, according to his plans, and he therefore gave free rein to his implicit and sincere belief that some men and women should be killed for their own good. The doctrine of blood atonement is illustrated by a joke Brigham Young told in one of his sermons: "And I some expect that many will be brought into close places, as the Jew was by the Catholic priest. The Jew fell through the ice, and was about to drown, and implored the Catholic priest to pull him out. 'I cannot,' said the priest, 'except you repent, and become a Christian.' Said the Jew, 'Pull me out this once.' 'Do you believe in the Lord Jesus Christ, and the Holy Catholic Church?' asked the priest. The Jew answered, 'No, I do not.' 'Then you must stay there,' and the priest held him under the water awhile. 'Do you believe in Jesus Christ now?' 'O yes, take me out.' 'Well,' remarked the priest, 'thank God that another sinner has repented; you are safe now, and while you are safe I will send you right to heaven's gate,' and he gave the Jew a push under the ice." Tt was one of the limitations of Brigham Young's mind that he himself always preferred a dead saint to a living sinner. That this doctrine of blood atonement created terror of conscience among the Saints and led to self-slaughter in the cause of righteousness, is illustrated by one story told bv a former Mormon leader. One of the wives of a Mormon of Salt Lake City was unfaithful to him while he was on a mission in foreign lands. __________ 5 Journal of Discourses, vol. 4, pp. 219-220. [Werner, 1925: p. 405] When he returned, the Church was in the throes of the Reformation, and his wife believed that she was doomed to lose the right to those children she had borne her husband in lawful wedlock, and that she would be separated from him and from them in eternity. She told her husband of her fears and of her sin, and he agreed with her that the fears were justified and the sin awful. She sat on her husband's knee and embraced him as she had never done before, while, as he returned her kisses, he cut her throat and thereby sent her spirit to the gods in all its former purity. The Reformation caused Mormons to confess all the sins they could think of, but Brigham Young was forced to admit in a sermon that "there has been more confessing than forsaking." Another effect of the Reformation was the death of its author, Jedediah M. Grant, who had suggested the Reformation to Brigham Young, was so busy baptizing Saints for the remission of their sins and therefore had to be in the water so much, that he contracted pneumonia and died in 1856, lamented by all the faithful. But the worst effect of the Reformation was its influence on the state of mind of the community. Murder became a righteous duty at times, and against sinners and enemies it was no longer regarded as a sin. Obedience to the leaders of the Church was considered a supreme duty, and the entire Mormon population was keyed up to a pitch of fiery faith by the psychological effect of the terrifying doctrine of blood atonement, and by the excitement which a renewal of righteousness caused in their minds. II Parley P. Pratt, one of the leading members of the Church, and its most active missionary, was accused early in 1857 Of seducing the wife of H. H. McLean, a merchant of San Francisco. Pratt, according to McLean, wished to make Mrs. McLean the seventh Mrs. Pratt, and Mrs. McLean was willing. But Mr. McLean was not, and in order to prevent his wife from joining the Mormons, her husband had adopted the course which was most-likely to throw her into their arms. He sent their children to her father's house in New Orleans, where she quickly__________ 6 The Rocky Mountain Saints, by T. B. H. Stenhouse, pp. 460-470. [Werner, 1925: p. 406] followed, and by pretending to repent of her Mormon tendencies, succeeded in getting her children back again. As soon as she had possession of them, she started for Utah. McLean pursued her. Meanwhile, Mrs. McLean had been corresponding with Parley Pratt, and Mr. McLean was looking for Mr. Pratt as well as for his wife and children. He intercepted a letter from Pratt to his wife, by which he discovered that they had an appointment to meet near Fort Gibson in the Cherokee Indian reservation. McLean followed and caught up with them. He brought legal action in Arkansas against Pratt, and great excitement was caused by the trial, in the course of which McLean introduced numerous cipher letters written by his wife and by Pratt. It was with difficulty that the judge kept the mob from lynching Pratt. McLean became so enraged that he drew his pistol in the court room and threatened to shoot Pratt there. Pratt was declared innocent of McLean’s charges against him and left town early in the morning. McLean followed, and near Van Buren, Arkansas, on May 14, 1857, he stabbed Pratt and killed him. A year before he was killed Parley Pratt had written an address which was delivered before the territorial legislature of Utah on "Marriage and Morals in Utah," in the course of which he approved with fervor the Bible penalties for adultery, which, he pointed out, consisted of stabbing or stoning the guilty party to death. This murder of one of their leaders enraged the Mormons, and they were disposed to have vengeance if possible. In September of 1857 a party of one hundred and thirty-six emigrants on their way from Arkansas to California passed through Utah. Those of the party who had not come from Arkansas were said to be from Missouri and Illinois, and the rumor was spread among the Mormons that these last were members of the mob that had murdered the Prophet Joseph Smith. As the emigrants passed through Utah, the Mormons were instructed to give them no aid, to sell them no provisions, and to adopt a negative hostility towards them in every way. At the time the army of the United States was on its way to Utah, and the Mormons were adopting an attitude of suspicious hostility towards all emigrants, but these who came directly from the state where Parley Pratt had just been killed, were regarded with special enmity, for the Mormons have never hesitated to attribute the sins of the fathers not only to the children, but also to the grandfathers, and even to the sisters, the cousins, and the aunts. [Werner, 1925: p. 407] The Mormons claimed that as these Arkansas emigrants made their way through Utah to the south they fought with Indians and poisoned wells with arsenic and cattle with strychnine. It has been established that some oxen died while these emigrants were in the neighborhood, but it was likely that they died of the poisonous weeds which were prevalent in the deserts of southern Utah. There was no evidence that the emigrants had either arsenic or strychnine in their baggage. On September 3, 1857, the emigrants arrived at Mountain Meadows. Mountain Meadows lay in a long valley. It was a level stretch of green seven miles long, entirely surrounded by hills and mountains, with a small gap at either end, leading out into the desert on one side and towards Jake Hamblin's ranch on the other. A small stream ran through the meadows, and near this the emigrants camped. At daybreak on Monday, September 7, as they were lighting their camp fires for breakfast, the emigrants were fired upon by Indians and white men dressed as Indians. More than twenty were killed and wounded, and the cattle were driven off by their assailants. The surviving emigrants barricaded themselves behind their wagons and prepared to withstand a siege. The attacking party retired to the hills and shot down on the emigrants who showed their heads outside their entrenchment. Soon the Arkansas people began to suffer from lack of water, for it was impossible to get any from the near-by stream until after dark, and then the risk of being shot in the attempt was great. After four days of siege, a wagon with a flag of truce approached the emigrants' corral. John D. Lee came to offer them protection if they would surrender their arms and ammunition. They consented to do this, after he had informed them that he was a Mormon and would take them to the nearest Mormon settlement, Cedar City, where they would be safe from the "Indians" who had attacked them. All the weapons were then placed in one wagon, and the wounded and children were placed in special wagons. The Mormon troops whom Lee had brought with him then opened order, and the emigrants marched with Mormons on either side of them, first the women, and then the men. As soon as they had marched a short distance, the Mormon guards turned on the emigrants and shot every one of them dead. Meanwhile, Lee, with several assistants, had taken charge of the wagons with the wounded and the children. When they heard the guns of their companions, Lee and his assistants shot into [Werner, 1925: p. 408] the wagons of wounded and children. McCurdy, one of Lee's assistants, approached a wagon containing sick and wounded, raised his rifle and said, "O Lord, my God, receive their spirits, it is for thy Kingdom that I do this." Thereupon he shot a man whose head was lying on another's breast and killed both with one ball. Indians and Mormons joined Lee and killed the rest of the sick and wounded, after they had finished with those capable of resistance. All except seventeen small children, who were too young to be able to describe the massacre, were killed. After the sick, the wounded, and the children had been killed, the Mormons took breakfast, and, having finished their meal, returned to bury the dead. But while the white men had been eating, the Indians had been stripping the bodies of men and women of their clothes and their valuables. The skulls of the emigrants had been battered in, and their scalps removed along with their clothes, so that naked and mutilated bodies lay strewn about the meadows in horrible disorder. Lee and his associates then told the Mormons under their command that they must tell no one, not even their wives, what had happened, and that if they were ever questioned concerning this massacre, they must attribute everything to the Indians. The bodies were then piled in heaps and covered with dirt, which the rain and the wolves soon removed. A few days before this massacre at Mountain Meadows a messenger had been sent to Brigham Young asking what the policy towards the emigrants should be. The messenger arrived in Cedar City again a few days after the massacre with an order from Brigham Young to allow the emigrants to pass through unmolested. The Mormon leaders of the southern district who had issued the orders for the massacre and carried out their execution, Isaac C. Haight, John M. Higbee, John D. Lee, and William C. Dame, were then worried about the righteousness of their action and its possible consequences. They sent Lee to report the massacre to Brigham Young, and to ask for his advice. Lee acted throughout, he claimed later in his confession, on the orders of Isaac C. Haight, who was his superior in the Church hierarchy, and who had promised him both celestial reward and temporal benefit if the emigrants were properly killed. Lee started on his ten days' journey from Cedar City to Brigham Young's office. He said later that as soon as he could see Brigham Young, he gave him all the details of the massacre, and that, [Werner, 1925: p. 409] "when he heard my story he wept like a child, walked the floor, and wrung his hands in bitter anguish...." [7] When Lee had finished his story, he wrote later, Brigham Young said: "This is the most unfortunate affair that ever befell the Church. I am afraid of treachery among the brethren that were there. If any one tells this thing so that it will become public, it will work us great injury. I want you to understand now, that you are never to tell this again, not even to Heber C. Kimball. It must be kept a secret among ourselves. When you get home, I want you to sit down and write a long letter, and give me an account of the affair, charging it to the Indians. You sign the letter as Farmer to the Indians, and direct it to me as Indian Agent. I can then make use of such a letter to keep off all damaging and troublesome inquiries." [8] Brigham Young then added: "If only men bad been killed, I would not have cared so much; but the killing of the women and children is the sin of it. I suppose the men were a hard set, but it is hard to kill women and children for the sins of the men. This whole thing stands before me like a horrid vision." The next morning when Lee called on Brigham Young again, the Prophet and President said: "I have made that matter a subject of prayer. I went right to God with it, and asked Him to take the horrid vision from my sight, if it was a righteous thing that my people had done in killing those people at the Mountain Meadows. God answered me, and at once the vision was removed. I have evidence from God that He has overruled it all for good, and the action was a righteous one and well intended. The brethren acted from pure motives. The only trouble is they acted a little prematurely; they were a little ahead of time. I sustain you and all the brethren for what they did. All that I fear is treachery on the part of some one who took a part with you, but we will look to that." For many years after the Mountain Meadows Massacre Brig- ham Young and John D. Lee were on terms of friendship. In his testimony before the Third District Court of Utah James __________ 7 The Lee Trial! An Expose of the Mountain Meadows Massacre, by the Salt Lake Daily Tribune Reporter, p. 9. 8 Lee's Mormonism Unveiled, pp. 252-253. [Werner, 1925: p. 410] McGuffie, a faithful Mormon, was asked: "What I want to get at is whether you know, of your own knowledge, that after that massacre John D. Lee continued to be on terms of friendship with the President of the Church?" "Oh, yes," he answered, "and got two more women after that: got two at a lick -- an English girl; she died." Brigham Young sent his report as Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Utah Territory to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs at Washington on January 6, 1858, and in it he summed up the Mountain Meadows Massacre with this explanatory statement: "On or about the middle of last September a company of emigrants traveling the southern route to California, poisoned the meat of an ox that died, and gave it to the Indians to eat, causing the immediate death of four of their tribe, and poisoning several others. This company also poisoned the water where they were encamped. This occurred at Corn Creek, fifteen miles south of Fillmore City. This conduct so enraged the Indians, that they immediately took measures for revenge.... Lamentable as this case truly is, it is only the natural consequence of that fatal policy which treats the Indians like the wolves, or other ferocious beasts. I have vainly remonstrated for years with travelers against pursuing so suicidal a policy, and repeatedly advised the Government of its fatal tendency. It is not always upon the heads of the individuals who commit such crimes that such condign punishment is visited, but more frequently the next company that follows in their fatal path become the unsuspecting victims, though peradventure perfectly innocent." Perhaps this explanation of the Mountain Meadows Massacre would have been accepted as the truth, but, unfortunately for the Mormon position, there existed those seventeen small children, who were believed to be living with the Indians who had massacred their parents. Relatives and friends in Arkansas urged the federal government to search for these children, and in the course of the search it was found that the children were living with Mormons, and not with Indians, Further investigation led to the suspicion that the Mormons were involved in the massacre. Dr. J. Forney, successor to Brigham Young as Superintendent of Indian Affairs, gathered the children together, and he found that they ranged from three to seven years of age. They remembered only their first names, and that their fathers, mothers, brothers, [Werner, 1925: p. 411] and sisters had been killed. They were returned to relatives in Arkansas in June, 1859. Several years after the massacre a military detachment was sent to Mountain Meadows to bury the bones of the emigrants. Major Carlton, commander of this expedition, found the bones uncovered by wolves. After his men had buried them, they erected a monument, and on one of the rocks they cut the words, "Here lie the bones of 120 men, women, and children, from Arkansas, murdered on the 10th day of September, 1857." And upon a cross bar, they painted: "Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord, and I will repay it." This monument was destroyed soon after the next visit of Brigham Young to that section of Utah. Meanwhile, John D. Lee and Brigham Young continued to be friends. Whenever Brigham Young and his large retinue visited Cedar City, Lee entertained them. Then, seventeen years after the massacre, Lee was suddenly cut off from the Church, and no explanation was offered for the action. Soon afterwards, on November 9, 1874, Lee was arrested and taken to Fort Cameron, Beaver County, Utah. When Lee was excommunicated, Brigham Young had informed his wives that they were at liberty to leave him, and eleven of them promptly did so. Judge Cradlebaugh, federal judge for Utah Territory, had held an investigation into the massacre two years after it was committed, but he was not able to get information sufficient to warrant indictments. It was not until a bill was passed authorizing federal officers in Utah to impanel jurors that any indictments could be returned by non- Mormon grand jurors. John D. Lee was tried for murder in July, 1875. The jury was made up of a majority of Mormons, and finally they failed to agree. In September, 1876, Lee was tried again, and this time the Church, which had supported him at the first trial, withdrew its support. The facts brought out at the first trial had aroused resentment throughout the country, and news and comment on the trial were printed in newspapers everywhere. Many editorial writers suggested that if Lee were acquitted, he should be lynched. The disagreement of the Mormon jury at the first trial also led newspapers to suggest that justice was impossible in Brigham Young's stronghold. Brigham Young and the Church leaders came to the conclusion that it would be wise for the Church to withdraw any influence on the jurors at the second trial, and they offered up Lee as a sacrifice to justice. At his second trial Lee [Werner, 1925: p. 412] was convicted of murder in the first degree and sentenced to be shot at the scene of the massacre. While he was in prison awaiting execution, John D. Lee wrote his confessions, which he entrusted to his lawyer, W. W. Bishop, who published them some years after Lee's death under the title,, Mormonism Unveiled. "I once thought," wrote Lee, "that I never could be induced to occupy the position that I now do, to expose the wickedness and corruption of the man whom I once looked upon as my spiritual guide, as I then considered Brigham Young to be. Nothing could have compelled me to this course save an honest sense of the duty I owe myself, my God, the people at large, and my brethren and sisters who are treading the downward path that will lead them to irretrievable ruin, unless they retrace their steps and throw off the yoke of the tyrant, who has long usurped the right of rule that justly belongs to the son of Joseph, the Prophet." This was a great change from Lee's former attitude, which was described by one who knew him: "Lee is a good, kind-hearted fellow, who would share his last biscuit with a fellow-traveler on the plains, but at the next instant, if Brigham Young said so, he would cut that fellow-traveler's throat." John D. Lee had decided to betray Brigham Young, because Brigham Young had betrayed John D. Lee by delivering him as a sacrifice to save the name of the Church. This sudden thrust into the dungeons to await the lions of the law opened Lee's eyes to past incidents. He now saw without the eye of faith, but with the eye of and the change in the point of view made him realize the significance of many events which he had previously accepted with unquestioning confidence. In September, 1857, according to Lee's own story, he was sent for by the Mormon military commander of southern Utah, Isaac C. Haight. The two men met at Haight's house and went from there to the Old Iron Works near Cedar City, where they spent the night under the stars talking. "After we got to the Iron Works," wrote Lee, "Haight told me all about the train of emigrants. He said (and I then believed every word that he spoke, for I believed it was an impossible thing for one so high in the Priesthood as he was, to be guilty of falsehood) that the emigrants were a rough and abusive set of men. That they had, while traveling through Utah, been very abusive to all the Mormons they met. That they had insulted, outraged, and ravished many of the Mormon women. That the abuses heaped upon the [Werner, 1925: p. 413] people by the emigrants during their trip from Provo to Cedar City, had been constant and shameful; that they had burned fences and destroyed growing crops; that at many points on the road they had poisoned the water, so that all people and stock that drank of the water became sick, and many had died from the effects of poison. These vile Gentiles publicly proclaimed that they had the very pistol with which the Prophet Joseph was murdered, and had threatened to kill Brigham Young and all of the Apostles. That when in Cedar City they said they would have friends in Utah who would hang Brigham Young by the neck until lie was dead, before snow fell again in the Territory! They also said that Johnston was coming, with his army, from the East, and they were going to return from California with soldiers, as soon as possible, and would then desolate the land, and kill every damned Mormon man, woman and child that they could find in Utah." Haight told Lee that it had been decided to arm the Indians, to give them food and ammunition, and to set them, upon the party of wicked emigrants. He did not say who had decided this, but he pointed out that Brigham Young had declared martial law in the Territory because of the advancing expedition of United States troops, and that therefore these emigrants had no right to travel through the Territory without a pass from Brigham Young Haight then said that it was Lee's job to round up the Indians, and to tell them that the Mormons were at war with the "Mericats," which was the Indian nickname for Americans. "I asked him,” wrote Lee, "if it would not have been better to first send to Brigham Young for instructions, and find out what he thought about the matter." "No," answered Haight, "that is unnecessary, we are acting by orders." After he had received these instructions from Haight, Lee joined the Indians, and he found that they had already attacked the emigrants. He camped with them, and he wrote of his experience the first night: "I spent one of the most miserable nights there that I ever passed in my life. I spent much of the night in tears and at prayer. I wrestled with God for wisdom to guide me. I asked for some sign, some evidence that would satisfy me that my mission was of Heaven, but I got no satisfaction from God." On the following day Lee and a detachment of Mormons and Indians made the truce with the emigrants, and killed them. The night before the final deception and murder of the emigrants Lee and his Mormon companions knelt in a circle, with [Werner, 1925: p. 414] elbows touching, and prayed for divine aid and guidance. When they arose, Major Higbee said, "I have the evidence of God's approval of our mission. It is God's will that we carry out our instructions to the letter." "It helps a man a great deal in a fight," Lee wrote in his confession, "to know that God is on his side." It is probable that the direction of this massacre was the work of Isaac C. Haight, who was the leader of the Church in the district where it took place, and who used John D. Lee to carry it out. The men and women of this southern district of Utah had been aroused to fear and antagonism by the impending arrival of -United States troops, whose purpose they did not know, and by the rumors circulated concerning the depredations of the emigrants. The state of mind in the neighborhood of Mountain Meadows is illustrated admirably in a sermon which George A. Smith delivered a few days after the massacre took place, but before news of it had reached Salt Lake City. Smith had just returned from a trip to Cedar City and the Mountain Meadows district. Later it was said that he bore orders from Brigham Young for the massacre, but there was no evidence for this accusation. Smith visited Parowan, Iron County, where he found the militia preparing for active operations. "They had assembled together," he said, "under the impression that their country was about to be invaded by an army from the United States, and that it was necessary to make preparation by examining each other's arms, and to make everything ready by preparing to strike in any direction and march to such places as might be necessary in the defense of their homes.... They were willing at any moment to touch fire to their homes, and hide themselves in the mountains, and to defend their country to the very last extremity." Wherever he went, George A. Smith found the same preparations. "They had heard," he said of the people of Penter, "they were going to have an army of 600 dragoons come down from the East on to the town. The Major seemed very sanguine about the matter. I asked him, if this rumor should prove true, if he was not going to wait for instructions. He replied, There was no time to wait for any instructions; and he was going to take his battalion and use them up before they could get down through the kanyons; for, said he, if they are coming here, they are coming for no good." This spirit led George A. Smith to conclude: "There was only one thing that I dreaded, and that was a spirit [Werner, 1925: p. 415] in the breasts of some to wish that their enemies might come and give them a chance to fight and take vengeance for the cruelties that had been inflicted upon us in the States.... But I am perfectly aware that in all the settlements I visited in the south, Fillmore included, one single sentence is enough to put every man in motion. In fact, a word is enough to set in motion every man, or set a torch to every building, where the safety of this people is jeopardized." [9] The emigrants from Arkansas and Missouri had the misfortune to pass through these settlements at the worst possible moment for their safety. It required only the rumor that some of them were the murderers of Joseph Smith and that all of them were the enemies of the Mormons and friends of the oncoming United States forces, to work up into a frenzy of recrimination those Mormons who were thirsting for revenge and anxious to protect themselves from dangers which they were anticipating. Brigham Young was never accused, even by John D. Lee, of direct responsibility for the massacre at Mountain Meadows. For Lee's second trial Brigham Young sent a written deposition of his testimony and examination by a lawyer, for he claimed that his health and his age -- he was then seventy-five years old -- prevented him from traveling to Beaver County, where the trial was held. In this examination, which was not admitted for the defense at the first trial, but which was introduced and admitted for the prosecution at the second, Brigham Young was asked: "Did John D. Lee report to you at any time after this massacre what had been done at that massacre, and if so, what did you reply to him in reference thereto?" He answered: "Within some two or three months after the massacre he called at my office and had much to say with regard to the Indians, their being stirred up to anger and threatening the settlements of the whites, and then commenced giving an account of the massacre. I told him to stop, as from what I had already heard by rumor, I did not wish my feelings harrowed up with a recital of detail." But Brigham Young's feelings were not easily "harrowed up," and it was usually his desire to know the details of everything that happened in his demesne. Brigham Young shares in the responsibility for this massacre indirectly. He had frequently talked against Gentiles in the pulpit, and particularly against California emigrants. He had __________ 9 Journal of Discourses, vol. 5, pp. 221-225. [Werner, 1925: p. 416] also caused his people to believe that a man who killed a Gentile or an apostate Mormon was no more than the instrument of God, and that his responsibility was no greater than the knife which was used to slit the throat or the bullet that was fired at the victim. In the excitement of the time of stress Brigham Young's assistants interpreted his general philosophy literally, and their assistants, the common people, were subject to pressure that kept them obedient to their leaders. Nephi Johnson, who was in the party of Mormons who executed the Mountain Meadows Massacre, testified at Lee's trial: "What do you mean by your evidence, where you were asked by Mr. Howard a question, and you answered that you would not have gone to the Meadows if you had known what was to be done? Answer: That is, not if I could help it. "State whether you were tinder any compulsion. Answer: I didn't consider it was safe for me to object. "Explain what you mean, that is what I want. Where was the danger -- who was the danger to come from if you objected -- from Haight or those around him -- from Indians, or from the emigrants? Answer: From the military officers. "Where? Answer: At Cedar City. "Was Haight one of those military officers? Answer: Yes, sir. "You thought it would not be safe for you to refuse, bad you any reasons to fear danger-had any persons ever been injured for not obeying, or anything of that kind? Answer: I don't want to answer. "It is necessary to the safety of the man I am defending, and I therefore insist upon an answer. Had any person ever been injured for not obeying, or anything of that kind? Answer: Yes, sir; they had." [10] When John D. Lee was finally arrested for the Mountain Meadows Massacre, he was found hiding in a chicken pen on his farm at Panguitch, Utah. He was forced out of his hiding-place by the marshal with some difficulty. He was calm, and asked to see the pistol that had been pointed at his head, remarking that it was the queerest-looking pistol he ever did see. His wives, however, were frantic with excitement, and William Stokes, the deputy marshal who arrested Lee, sent for a pitcher of wine to calm the women and refresh the soldiers. They all drank, and one of Lee's __________ 10 Mormonism Unveiled, p. 349. [Werner, 1925: p. 417] daughters, as she raised the pitcher, said: "Here's hoping that father will get away from you, and that if he does, you will not catch him again till hell freezes over." "Drink hearty, Miss," answered Stokes. The rumor was circulated that an attempt would be made by some of Lee's army of sixty-four children to rescue him from the law, and he was guarded with extraordinary precautions. Lee was led to his execution by a strong guard of soldiers and a cortege of newspaper correspondents and lawyers. In the twenty years since the massacre the green valley of Mountain Meadows had changed to an arid plain. The pine boards for Lee's coffin were transported with the execution party, and the carpenters began hammering them into a coffin, while Lee sat a short distance away watching them with intense interest. A photographer took some pictures of the scene. Lee asked to talk to the photographer and said to him: "I want to ask a favor of you; I want you to furnish my three wives each a copy. Send them to Rachel A., Sarah C., and Emma B." Those were the only faithful wives left of the nineteen. The photographer promised to carry out this request, and then Lee posed for the photographs. He addressed the group of people about him, assuring them that he was innocent in intent, and that he had only obeyed the orders of his superiors and was the victim at a sacrifice. He said that he still believed in the divinity of Joseph Smith, but that he no longer believed in the virtue of Brigham Young. Then his eyes were blindfolded, and he sat on his own coffin. A Methodist minister delivered a fervent prayer, to which Lee listened attentively. "I ask one favor of the guards," he said, as soon as the prayer was finished, "spare my limbs and center my heart." He then straightened up, still sitting on his coffin, and said: "Let them shoot the balls through my heart. Don't let them mangle my body." The marshal assured him that the aim would be accurate. The command was given, "Ready, aim, fire." Five soldiers fired, and Lee fell back on the top of his own coffin without a moan, as the echo of the shots reverberated through the surrounding hills.... (from M. R. Werner's 1925 book, Brigham Young) |

|

Extract from R. B. West (1957) pp. 271-288